Intuition: Completing the Square

Today we learned about completing the square. This is essential to finding the quadratic formula, and can be used to solve quadratic equations on its own. The important part of this is that these methods have a 100% success rate, meaning that you don’t have to guess to solve a quadratic.

The Goal

Completing the square makes it so that there is only one \(x\) in the whole equation.

The above sentence may be kind of confusing, so let me explain:

This equation has two \(x\)s in it:

\[ax^2 + bx + c = 0\]Meanwhile, this equation (NOT derived from the equation above) has one \(x\) in it:

\[a(x+b)^2+c=0\]The advantage of the second equation is that now, we can just move some stuff over, square root everything, and then we get only one \(x\) term that is linear.

The Process

For now, assume \(a = 1\).

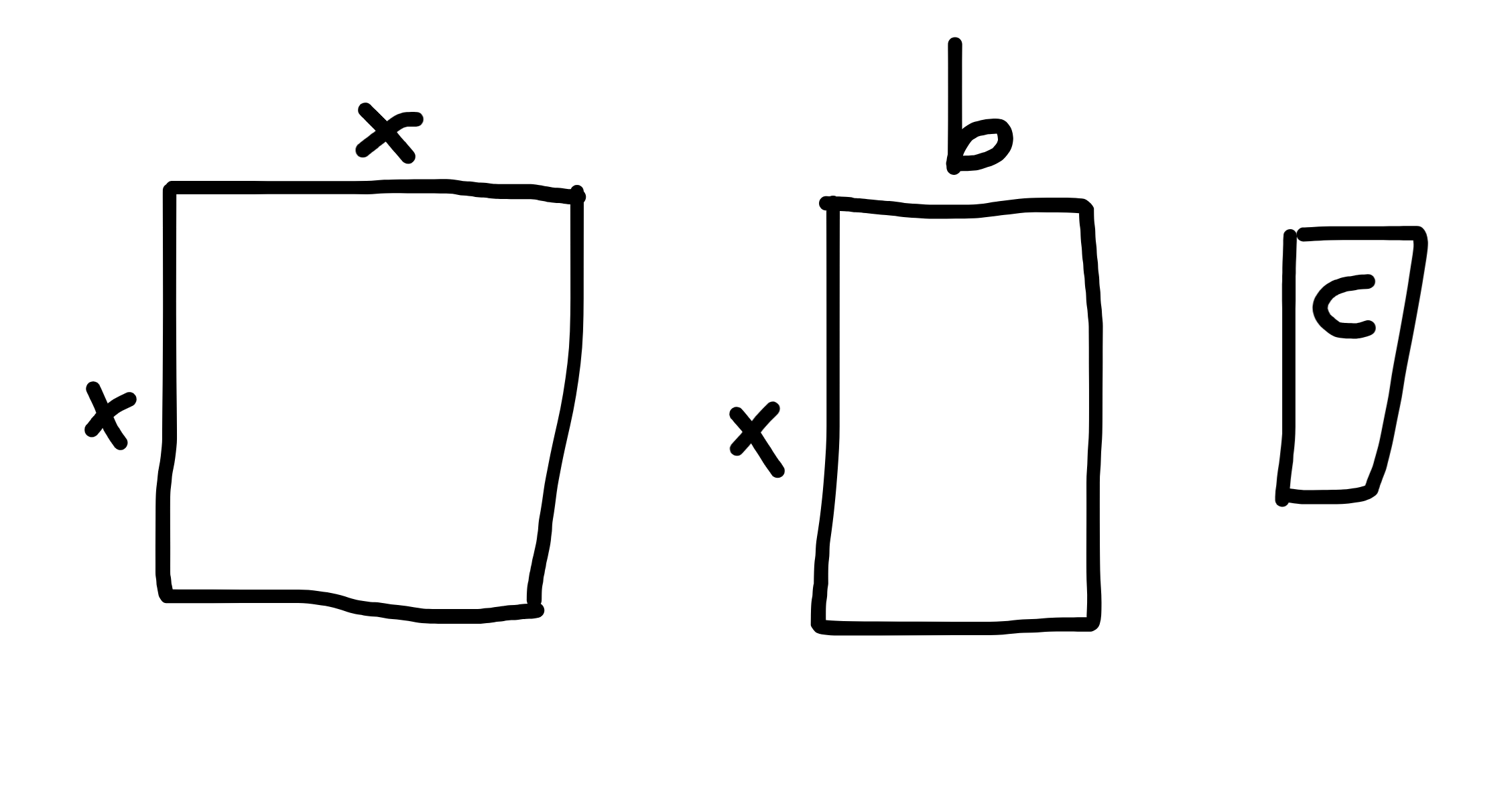

This is what \(x^2 + bx + c\) visually looks like (where area is the number):

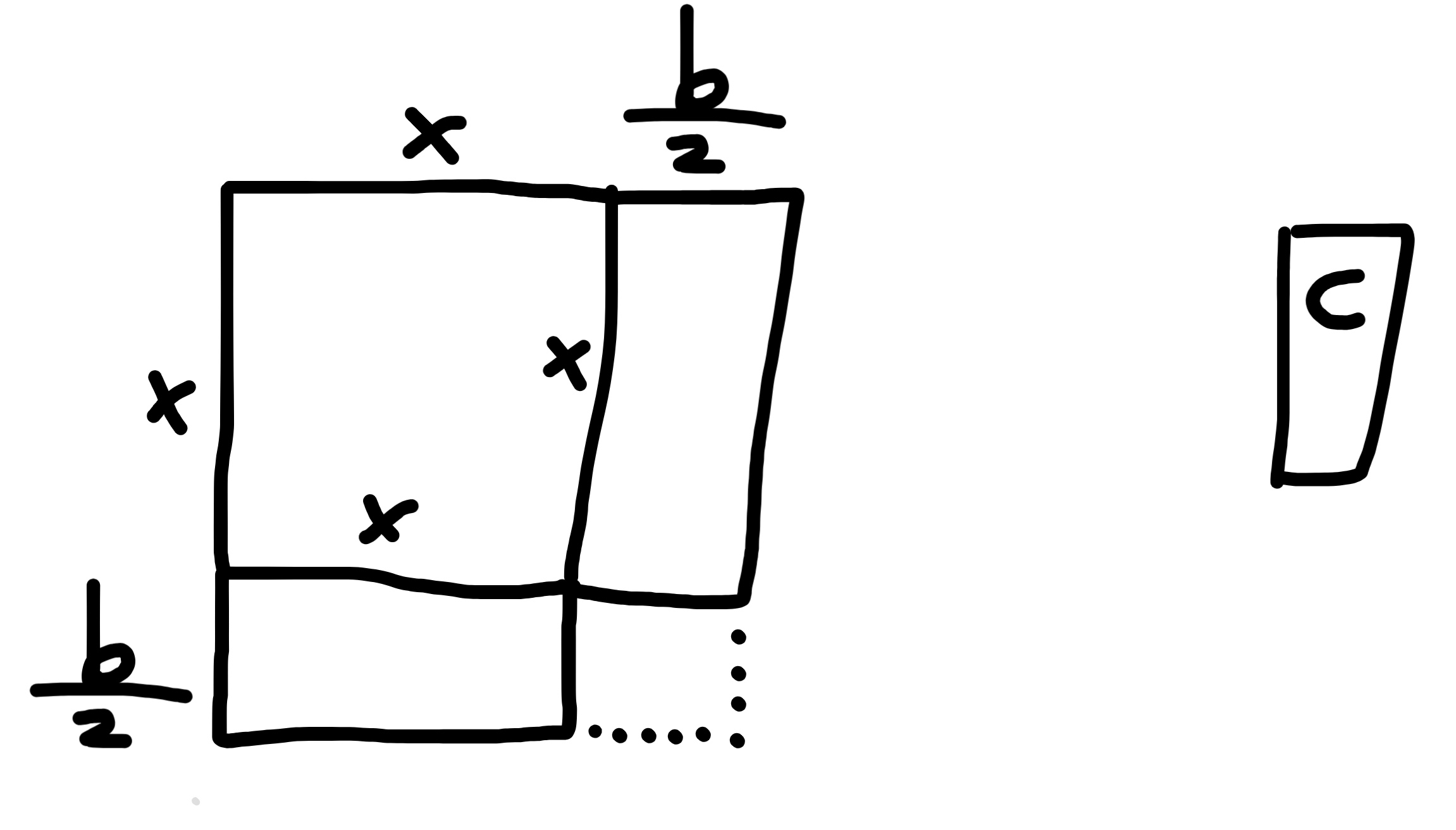

To collapse it into a square, we need some way to get it so that both sides are the same, plus some area for the remaining \(c\) part. The \(x^2\) is already a square, so we just need to somehow split up the \(bx\) part and put it on the \(x^2\) part. If we put something on one of the sides, that same thing should go on the other sides, so it makes sense to split \(bx\) into two parts and put one slice on each side of \(x^2\). Now, it looks like this:

Once we do this, we can just find the last missing part of the square. This comes out to \(\frac{b^2}{4}\).

Writing this in equation form, we get this:

\(x^2 + bx + c = 0\) (starting equation)

\(x^2 + 2(\frac{b}{2}x) + c = 0\) (split \(bx\) into two parts)

\(x^2 + 2(\frac{b}{2}x) + \frac{b^2}{4} - \frac{b^2}{4} + c\) (fill in the square in the edge)

\((x + \frac{b}{2})^2 + c - \frac{b^2}{4}\) (make the square a square)

If \(a \neq 1\), just divide the whole thing by \(a\).

Conclusion

Completing the square is very important, but there are still things like the quadratic equation up ahead. The quadratic equation gives you the solution directly, instead of completing the square, where you still need to square root both sides. Stick around for that!